Introduction

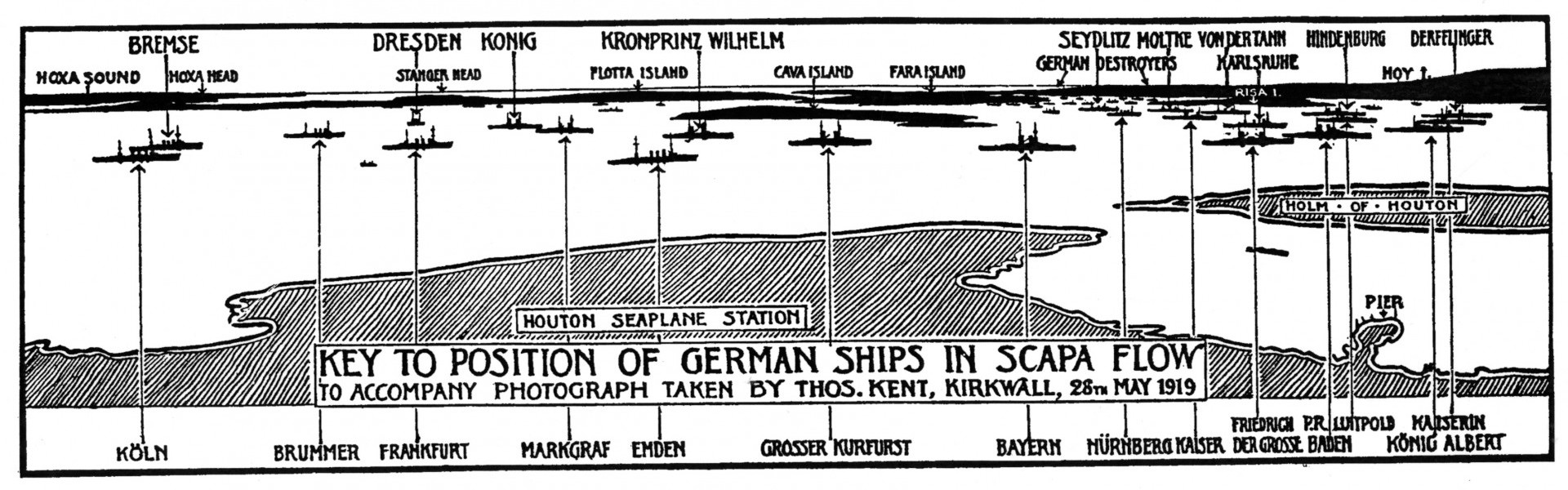

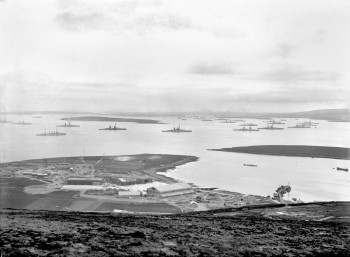

On the 23rd November 1918, 20 German destroyers arrived in Scapa Flow.

These were followed over the next few days by more ships: destroyers, light cruisers, battle-cruisers and battleships. The battleship Baden was the last to arrive on 9th January 1919.

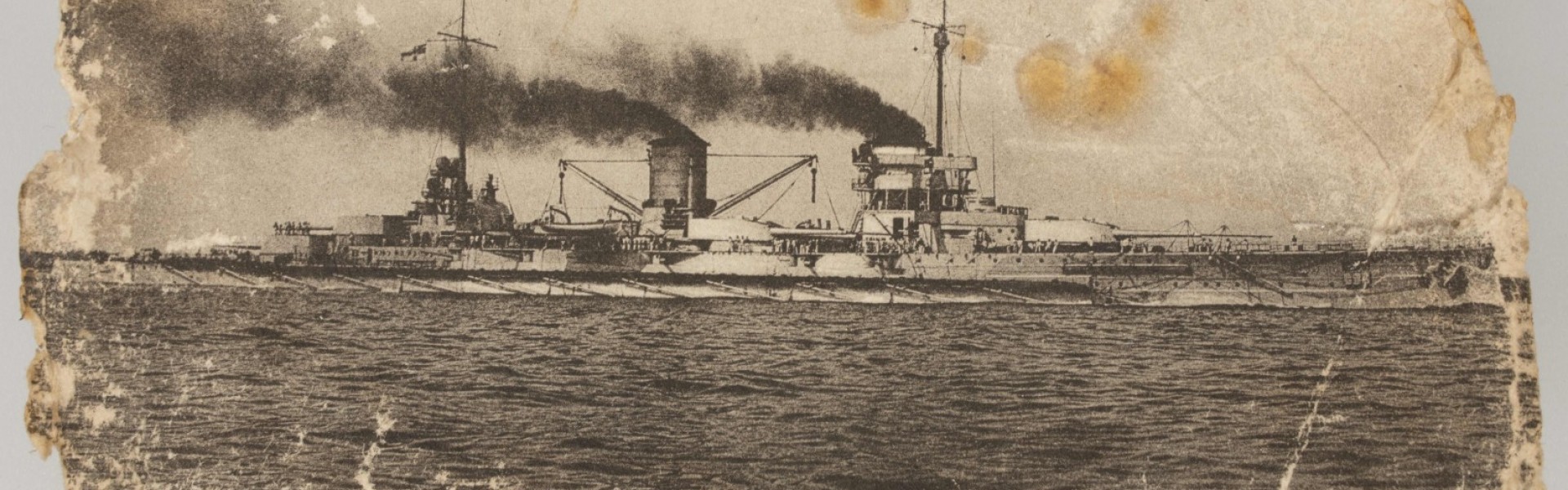

These 74 ships - once the pride of the German High Seas Fleet - were interned by the Allies as part of the Armistice agreement while peace talks were carried out.

Their future was uncertain.

The man who was in charge of the ships, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, was not kept informed about how the peace talks were progressing. The Armistice was due to run out on the 21st June 1919 and the latest news that von Reuter had was from a copy of The Times newspaper that was five days old.

The German government had resigned after rejecting the harsh terms laid down by Britain and France, which would cause the collapse of the German economy and had the potential to start a revolution. What von Reuter did not know was that the Armistice had been extended to the 23rd June while a new government was sworn in. When von Reuter saw the British 1st Battle Squadron leave Scapa Flow for torpedo practice on the morning of the 21st June, he took the opportunity to issue the prearranged signal for the fleet to be scuttled.

Between 12:00 and 17:00 that Saturday afternoon, 52 of the 74 ships sank. Others were beached by the Royal Navy who had rushed back on hearing the news.

Rear Admiral von Reuter always maintained that he knew nothing of the extension of the Armistice, claiming he had sunk his ships to prevent them from falling into the hands of Germany’s enemies.

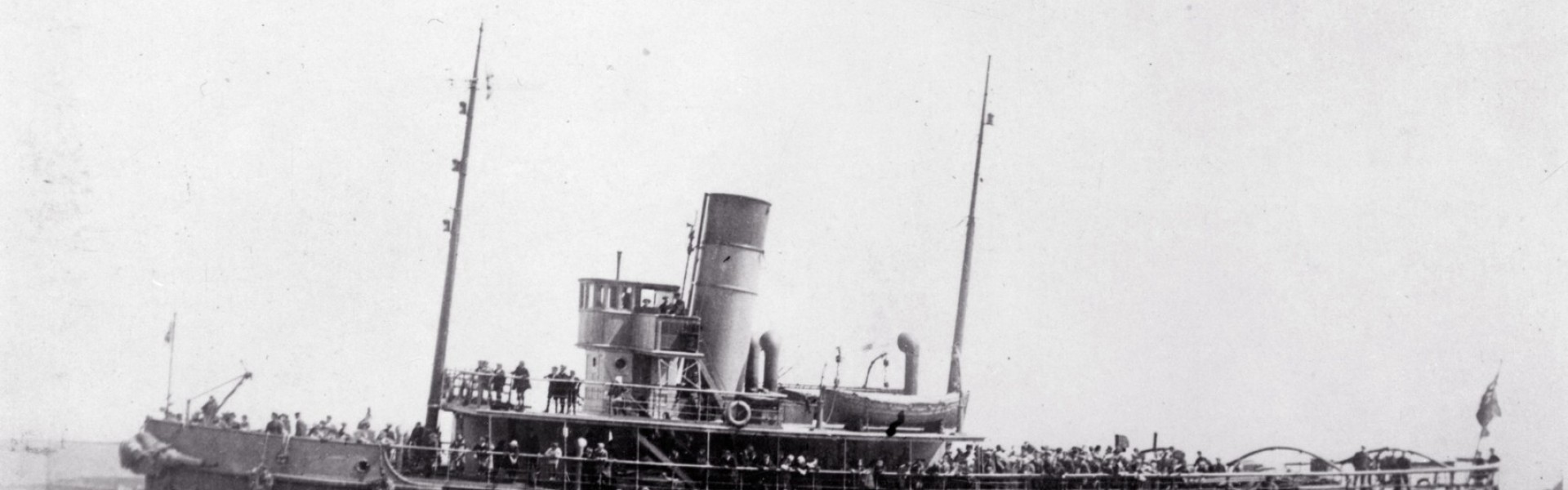

The Flying Kestrel was a supply ship that brought fresh water to both the Royal Navy and German Fleet. Trading went on between supply vessels and the German crew.

The local newspaper, The Orcadian, claimed that the going rate for an Iron Cross medal was a bar of soap.

These souvenirs would most likely have been sold or bartered once back on shore in Stromness.

The dramatic end to the German Fleet was seen up-close by children from Stromness Public School. Around 200 of the older Primary School pupils and the Secondary School pupils were booked to go on a tour of the ships on the 21st June 1919.

As they sailed around the rusting warships on board the supply ship Flying Kestrel, the German Fleet started sinking all around them. Some heard (and saw) German sailors being shot in the chaos that followed.

The children were returned safely back to Stromness where their parents were anxiously awaiting them.

The Admiralty had sent salvage experts to inspect the situation, who declared that the large ships, lying upside down, could never be moved. Their report stated:

“There can be no question of salving the ships. And, as they offer no hindrance to navigation they need not be blown up. Where they were sunk, there they will rest and rust.”

(Jellicoe, Nicholas (2019) 'The Last Days of the High Seas Fleet; From Mutiny to Scapa Flow')

Nineteen beached destroyers were raised and towed away by the Royal Navy, although one attempt to tow seven destroyers to Rosyth in February 1920 ended in disaster when a storm blew up unexpectedly and the tow lines parted.

One, B98 (not originally one of the interned ships, but the mail ship which arrived on 21st June and was seized by the Royal Navy) ran aground on Sanday, while another sank after being towed back to Scapa Flow.

The others were lost. The incident was quickly hushed-up by the Admiralty. Three light cruisers and the battleship Baden were also raised and towed away by the navy. The brand-new battleship was given to the Royal Navy and was sunk off Cornwall when it was used for gunnery practice.

The destroyer G92 was refloated and towed away for scrap in 1922. The identity of the salvager is not known for sure, but may have been the East Coast Wrecking Co. who were engaged raising blockships in the eastern channels into Scapa Flow.

Another destroyer, G89, was bought by a syndicate of Stromness businessmen, led by the blacksmith Jack Moar (originally from Hoy), called the Stromness Wrecking Company.

They paid the Admiralty around £200-£250 for the wreck that was lying in shallow water on the west side of Fara.

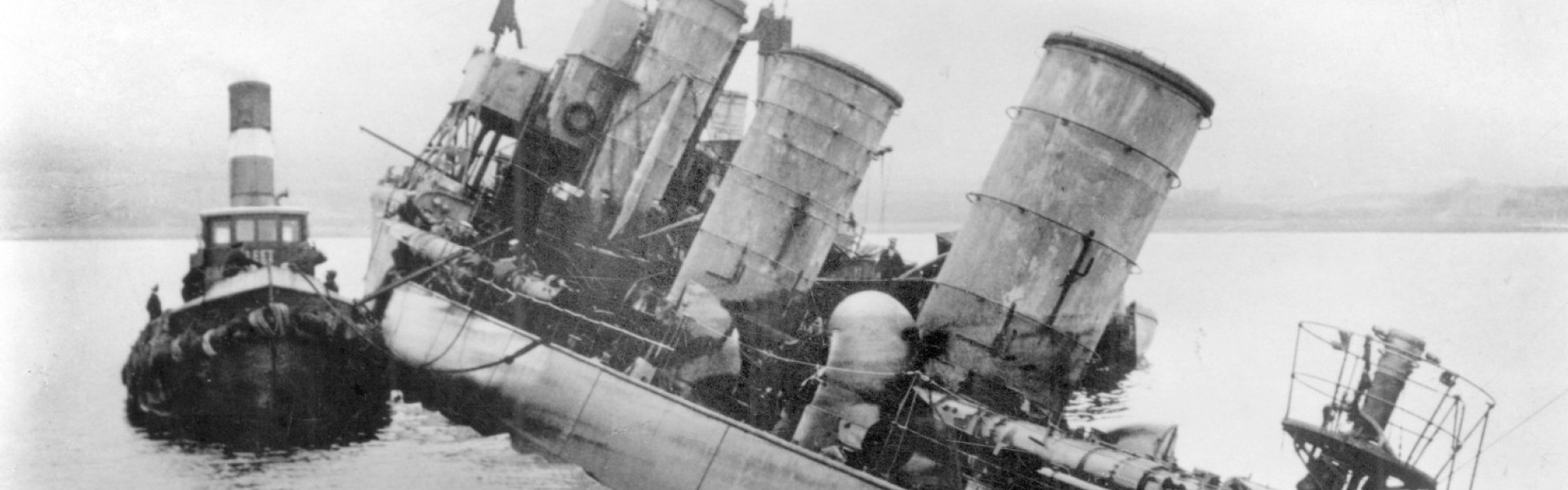

The G89 was raised on 10th December 1922 by pumping the bow and stern sections dry, but the midships section had been damaged on the rocky shore and leaked badly. The Stromness Wrecking Co. had hired two tugs from the Shetland firm J.W. Robertson. These ships, along with the syndicate’s own vessel Campania, and assisted by the passenger ships SS Hoy Head and SS Countess Cadogan, successfully towed the destroyer to Stromness.

The operation was directed by Capt. George Porteous from the bridge of the destroyer.

He used his knowledge of the seas around the area to catch the ebb tide and use it to bring the leaking destroyer (which was letting in water at a dangerous rate) into the harbour where it was beached on a sandbank at the North End.

It was floated up still further with the rising tide until it was beached at the North End at a place known as the ‘Reclamation’.

The destroyer was broken up where she lay and many of the parts recycled into useful household goods.

The brass boiler tubes were cut-down, polished and reused as curtain rods.

Her stripped hull would later be sold to the Cox & Danks salvage firm for £50.

J.W. Robertson of Shetland saw the potential for salvage and bought four destroyers from the Admiralty in 1923.

His company, named the Scapa Flow Salvage and Shipbreaking Co. used salvage barges to raise the destroyers and specially designed air bags (nicknamed ‘camels’) to give extra buoyancy.

All four destroyers were raised between August and December 1924.

But there was another salvage company who saw the potential of the Scapa Flow wrecks. Ernest Cox ran a scrap metal business, Cox & Danks, in London and a shipbreaker’s yard at Queensborough in Kent. Cox had founded the company with financial backing from his wife’s cousin, Tommy Danks, who Cox bought out in 1918. He was to pioneer salvage work in Scapa Flow for nearly a decade.

In early 1924 Cox & Danks bought 25 German destroyers and two battle-cruisers, Seyditz and Hindenburgh, from the Admiralty for £24,000.

Between 1924-26 they raised all 25 destroyers.

Cox had bought a floating dock which, ironically, had been seized from Germany as part of the compensation that Britain claimed for the scuttling of the fleet. It held a huge tubular chamber for pressure testing the hulls of U-boats.

Having scrapped the chamber, Cox had the dock cut down the middle to form two L shaped docks with winches running the full length of it. By threading steel wire underneath the destroyers he would use the rising tide to lift the vessel and then tow it into shallower water until it was fully beached. Mill Bay was used for this purpose and all the destroyers that Cox & Danks raised were broken up on the shore.

Ernest Cox was a brilliant engineer who relished the challenge that the sunken German ships posed.

He had a good knowledge of breaking up ships, having already scrapped two old Royal Navy battleships, Orion and Erin.

But he had no experience raising a sunken ship. He knew that a battleship had been raised in Italy using compressed air pumped into the hull, but this ship was upright, while the German ships were on their sides or upside-down.

No one had ever attempted anything quite like this before.

Cox established a system where long tubes called ‘air-locks’ were fitted together in sections ashore and then towed out to the ship.

The air-lock was bolted onto the upturned hull of the ship and guy-ropes of steel wire were fastened from them to the hull for support.

This gave workers access to the bottom of the ship, where a hole was cut through the hull.

Air was pumped into the ship to push out water, letting a crew work inside the upside-down hull to seal up holes and to section it off into water-tight compartments. Once sealed, air was pumped into the hull, raising it to the surface. Obstructions were cut or blasted away from the floating hull by divers. The hull was allowed to sink in shallow water with a hard rocky bottom, to force parts of the superstructure up into the ship.

The salvage work brought great financial benefits to Orkney.

A base depot was established at Lyness, where there were old navy accommodation huts for the workforce.

The large ships were relieved of armour plate, guns, propellers and anything that would lighten the ship and bring in money quickly.

Cranes ran on railway tracks to lift scrap from ships onto Lyness Pier.

Cox had a reputation of working his men hard, but he would never ask a worker to do anything that he wouldn’t. Along with his chief salvage officer, Thomas McKenzie, Cox would carry out dangerous work during the salvaging. Despite being safety conscious there were some fatal accidents while salvaging the ships.

The salvage work cushioned Orkney from the economic depression between the World Wars.

At the height of the salvage operations Cox & Danks employed 200 men, mostly from Orkney.

There was a core of around 40 experienced, skilled workers who were not only paid well but also had paid holidays - something that was virtually unheard of in those days.

During the General Strike of 1926 the price of coal soared in price, going from £1 a ton to £4.15s.

Ever resourceful, Cox cut through the exposed side of the battle-cruiser Seydlitz to reveal her full coal bunkers. A ready-made coal mine.

As none of his workers joined the strike, he gave them all a three-week paid holiday for Christmas, which cost him £3,000.

Later, in June 1938, Metal Industries Ltd. (who bought out Cox and Danks in 1933) gave a large pay increase.

The highest earners - the men carrying out the most dangerous jobs - received more than £10 a week. This was a first for manual workers in Orkney. It has been estimated that the salvaging of the German Fleet brought in more than £1.25 millions, the equivalent of £50-£60 millions in today’s money.

Once the ship had been refloated, and any obstructions and extra weight removed, she was ready for her last voyage. Each of the battleships and battle-cruisers were towed upside down to the Royal Naval dry dock at Rosyth where they were broken up. The one exception was the Hindenburg, which had sunk upright.

As compressed air in the hull had to be monitored and replaced if some escaped, there had to be a crew onboard.

This highly dangerous job was done by the ‘running crew’ of around 14 men who lived in huts on the upturned hull. These huts consisted of a kitchen, bunkhouse and mess room for the crew and the compressor powerhouse to pump the air.

Sudden gales saw the hull being swept by waves, flooding the accommodation hut and soaking the crew. Amazingly, no one was lost on these voyages.

Cox & Danks actually lost money on the salvage work at Scapa Flow.

With scrap prices fluctuating, Ernest Cox sold his interests to Metal Industries Ltd. in 1933.

Cox had raised 25 destroyers, 6 battleships/battlecruisers and the light cruiser Bremse, which was broken up at Lyness.

Metal Industries Ltd. made the salvage work pay, raising another battle-cruiser and 5 battleships between 1934-39.

The outbreak of World War II saw salvage work stop. The battle-cruiser Derfflinger remained at anchor, upside-down, behind the island of Rysa Little for the duration of the war. But the remaining workforce were not idle. They carried out salvage for the Royal Navy, including the towing and beaching of HMS Iron Duke when it was badly damaged in an air-raid on 17th October 1939. Without the Metal Industries Ltd. tugs the ship would have sunk, with the likelihood of considerable loss of life.

Metal Industries Ltd. never resumed salvage work after the war, saying that the three remaining battleships, Kaiserin, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf, and the four light cruisers, Karlsruhe, Dresden, Cöln and Brummer, were in too deep water to make salvaging profitable.

Metal Industries Ltd. sold out their salvage interests in these last 7 ships to their former diver, Arthur Nundy, who formed Nundy (Marine Metals) Ltd.

Now, instead of raising the ships they were blasted. Metal plate and non-ferrous metal were removed by a floating crane.

In 1971 Nundy sold out to Scapa Flow Salvage, run by David Nicol and Dougal Campbell. The process of blasting and lifting by crane continued. The scrap metal was shipped to Aberdeen and then on to the buyers by road.

This last salvage work benefited from a strange quirk of fate that made the metal more valuable.

Since nuclear bomb testing, and the use of nuclear bombs against Japan in 1945, all steel made after that date is slightly radioactive, due to the atmospheric radiation in the oxygen used in the smelting process.

This steel is not suitable for medical or scientific instruments that record radioactivity.

Pre-nuclear testing steel has no radioactive contamination and so is needed for delicate measuring equipment.

Legend has it that there is German Fleet steel in NASA’s space probe Voyager, but NASA has never confirmed this.

Salvage work is no longer carried out on the German wrecks. On 23rd May 2001, Historic Scotland (now Historic Environment Scotland) awarded the remaining 7 German wrecks ‘scheduled monument’ status. HES classified the remaining ships as scheduled ancient monuments in recognition of their cultural and historical significance. They now attract divers from all over the world, but while divers are allowed to visit the wrecks, removal of any artefact or souvenir is illegal and can incur heavy penalties.

The wrecks are now living artificial reefs, supporting a wealth of marine wildlife. They are a part of Scapa Flow’s ecosystem, as well as a living record of early 20th century maritime technology. Find out more about Scapa Flow's Living Wrecks in our online exhibition.

Introduction

On the evening of the 9th July 1917 the peace of Scapa Flow was shattered by a series of catastrophic explosions.

When the dust and smoke cleared, HMS Vanguard was no longer there.

The battleship and 843 of her crew had been lost.

There were three survivors, one of whom later died of his injuries.

James Tucket gave this eye witness account:

“I was coming along the upper deck when there were three tremendous flashes which seemed to reach the sky. Simultaneously three terrible explosions.

Under the impact Collingwood heeled over temporarily, then debris began to fall like hail – mostly pieces of steel. I tried to run for shelter but my legs would not work and I thought myself a cheap little coward.

"The Fleet was practically obliterated with a tremendous pall of smoke, which took a long time to lift. Pandemonium broke out, boats were lowered for survivors but alas, only mutilated bodies were picked up.

The big question came next. Which ship had gone up? No one knew until the C-in C made the recognition signal (which must be answered instantly). All answered except H.M.S. Vanguard.”

(Brown, M & Meehan P (1968) The Reminiscences of men and women who served in Scapa Flow in the two World Wars.)

A Royal Navy court enquiry decided that HMS Vanguard had been lost due to an internal explosion, caused by cordite ammunition, which could be very unstable.

This is the largest accidental loss of life suffered by the Royal Navy in the 20th century.

Attitudes have changed considerable over the last 100 years. Early salvage of the wreck is unknown, but a license to commercial salvage was granted to Arthur Nundy, of Nundy Marine Metals in 1957.

In 1971 Nundy sold the salvage rights to Dougall Campbell of Scapa Flow Salvage, who continued salvage work on the wreck until 1975.

In 2002 HMS Vanguard was designated a Controlled Site under the Protection of Military Remains Act of 1986 prohibiting recreational and commercial diving within a 200 metre exclusion zone of the wreck site.

She is marked by a buoy which carries a notice that the wreck is a war grave.

The VANGUARD 100 SURVEY

The HMS VANGUARD 100 Survey was organised to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the loss of the Vanguard. It was carried out between October 2016 and February 2017 under special license from the Secretary of State for Defence.

A group of specialist volunteer divers conducted the survey using state of the art, underwater surveying techniques to document the wreck site using videography, photography and 3D photogrammetry.

"The VANGUARD 100 survey used remote survey techniques to identify the extent of the wreckage and debris field. Specialist divers conducted underwater surveys of the entire site using underwater mapping and forensic diving techniques. The wreck was documented using videography, stills photography and 3D photogrammetry.

VANGUARD should continue to be treated as a site of huge historical importance. Notwithstanding her war grave status, she also has a substantial relevance to current naval safety. She is a time capsule into WWI naval architecture, and mid-20th century ship wreck salvage techniques. Methods used by the VANGUARD 100 survey team have been shown to be highly effective and should be widely communicated to benefit future wreck site surveys and wreck site management."

(Turton, E et al (2018) HMS Vanguard 100 Survey 2016 – 2017, Survey Report 2018)

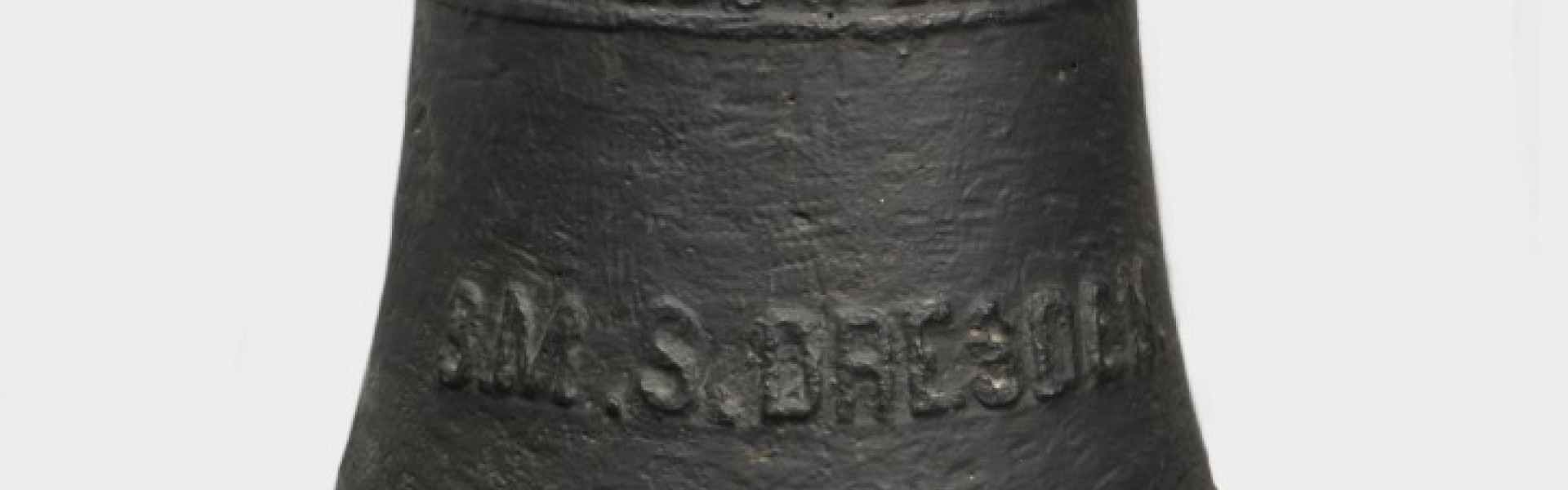

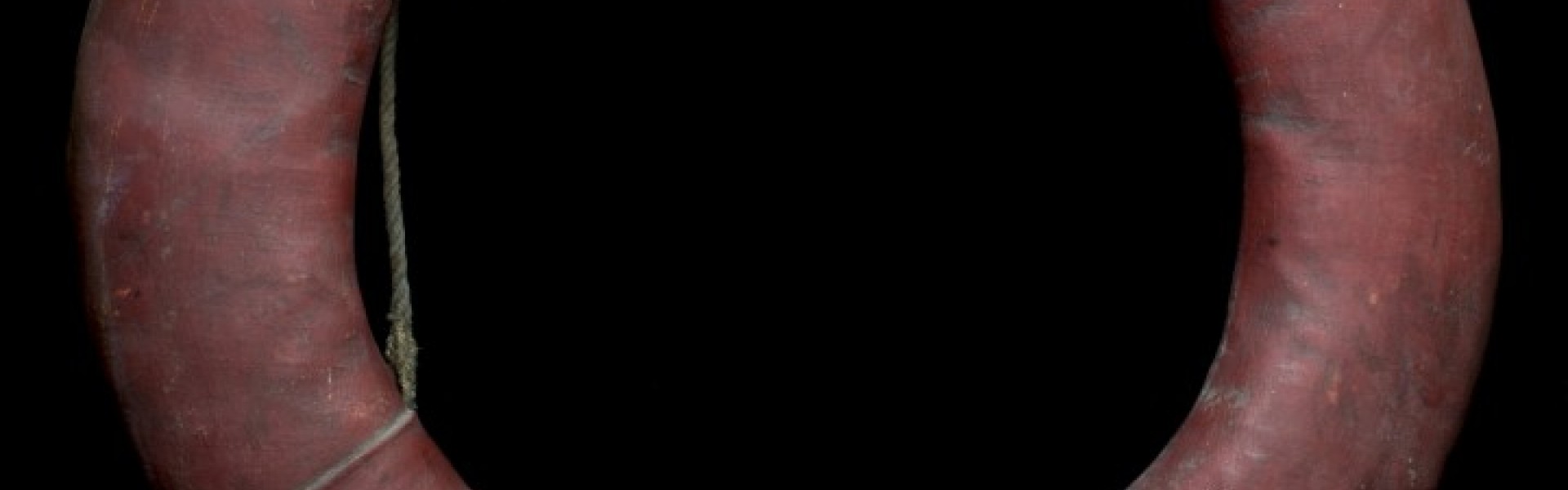

Stromness Museum has worked with researchers from 3DVisLab at the University of Dundee, Emily Turton, Ben Wade and other experts from The HMS Vanguard 100 Survey Team to take a closer look at our collection of Scapa Flow material. This collaboration has led to the successful identification of objects in our collection as objects from HMS Vanguard.

Many of these artefacts have been 3D scanned to produce photographic images. These images can be used to help increase our understanding of how these objects were used onboard the ship.

Exhibition objects

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3