Just after midnight on the 24th June 1919, four men were walking along the deck of HMS Resolution. A shot rang out and one of the men cried in pain and staggered sideways. His name was Kuno Eversberg and he had less than five days left to live.

During the scuttling of the Interned German Squadron (as it was officially known) the resulting chaos saw seven German sailors shot dead on 21st June; another died from his wounds the following day. The surrendering German sailors were taken onboard the battleships of the 1st Battle Squadron, where they were treated with sympathy. Then the order came from Rear Admiral Fremantle that they were to be treated as prisoners of war. The atmosphere changed and friendliness soon turned to contempt and violence. Most of the prisoners were then taken to Invergordon, where they were transferred to POW camps.

On board HMS Resolution there were around 80 German prisoners. The ship remained at Scapa Flow while they worked on the salvaging of the German Battleship SMS Baden. News of the German acceptance of the peace terms finally came through in the evening of 23rd June, which saw some modest celebrations onboard the ship.

At around 00:05 two German prisoners were being escorted under armed guard to the toilet. It was then that 19 year-old Kuno Eversberg was shot, the bullet passing through his body and lodging in the deck. He was taken to the ship's doctor before being transferred to the hospital ship, HMS Agadir, at 03:00. Here he was examined by Dr Bolton, who found that the bullet had passed through his bowels. In those days before antibiotics he knew that it was only a matter of time before infection set in. Eversberg died of peritonitis at 09:40 on 29th June.

The shooting had been reported to Rear Admiral Fremantle by Capt. Alington of HMS Resolution later on the 24th. Fremantle ordered an investigation, yet the ship sailed to Invergordon on the 30th June and the crew were given shore leave. On 2nd July Alington informed Fremantle that he could not identify the murderer. It was the 25th July before Fremantle informed his commanding officer, Admiral Madden, of the murder. Madden was furious that he had not been informed immediately and that a court of inquiry had not been ordered.

In response to a request from the German Government, Fremantle listed the German sailors killed during the scuttling. He didn't include one sailor whose body was never recovered, but he added Eversberg's name to the list of those "buried at Lyness". It was written at 17:25 on 29th June; the day of Eversberg's death. His body was still lying in a floating morgue at Lyness at that time.

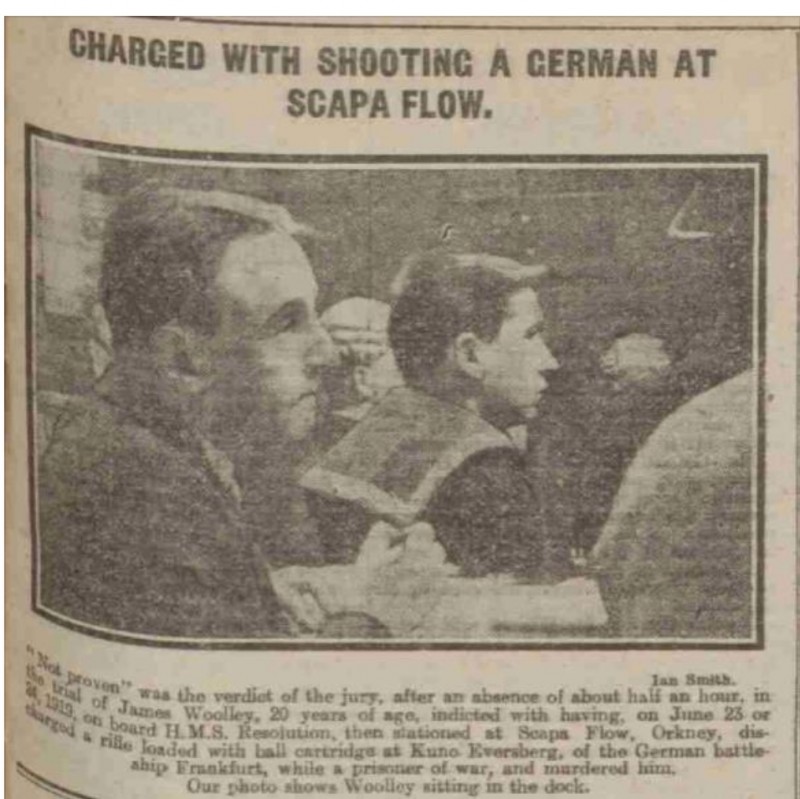

The court of inquiry proved useless, much to the increasing fury of Madden. A second one was held, where the name James Wooley was given in evidence as the murderer. Now there was the problem of apprehending Wooley, who was also 19 years old, as he had deserted after leaving the ship. He was eventually arrested and imprisoned in Chatham for desertion. Later he was charged with Eversberg's murder and sent to Kirkwall for the charges to be officially brought against him.

Wooley's trial for murder was at the High Court in Edinburgh on 9th February 1920. The court heard that he had gone to one of the drifters and had received brandy, which had been bartered from the German ships. In a drunken state Wooley said that he wanted a rifle in order to kill a German, any German, in revenge for two of his brothers who had been killed in the war. Another sailor, William Berry, had heard him say this and seen him with a rifle, lying alongside 'B' turret, waiting for a German prisoner to be brought out. The judge said that Berry deserved to be in the dock as an accomplice, as he admitted that he condoned the killing. A doctor who examined Wooley said that a head injury he had received as a boy had left him mentally unstable.

After just 25 minutes the jury returned a verdict of Not Proven; in Scottish law it means that there was not enough evidence for a secure conviction. Cheers broke out in the court and Wooley burst into tears. He was warmly congratulated by his friends, who slapped him on the back. It was too much to expect a British court to convict a British sailor of murdering a German after such a bitter and bloody war.

The Admiralty dismissed the evidence of mental instability as something not to be taken seriously. Wooley was discharged from the navy, although Berry was not punished for his complicity in the killing. The Admiralty reprimanded Capt. Alington for his handling of the shooting. Rear Admiral Fremantle was also reprimanded for not reporting the shooting to his commanding officer immediately, for not ordering a court of inquiry and for giving false information by adding Eversberg to the list of the dead killed during the scuttling. This led to the wrong date being put on Eversberg's gravestone.

Research by Kevin Heath brought this story back into the public domain and convinced the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to change the date on Eversberg's gravestone from 21st June to the 29th June 1919. Kuno Eversberg never received justice for his murder, but his story has at last been told.