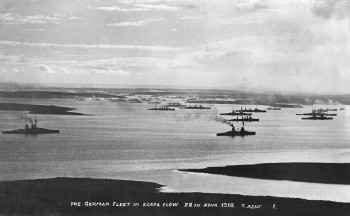

On the 23rd of November 2018 the first ships from the German High Seas Fleet were escorted into Scapa Flow by the British Grand Fleet and a representation of her allies. Over the next few weeks more German ships joined them until there total reached 74. They were to be interned here as part of the Armistice agreement until they took matters into their own hands on the 21st June 1919.

At 12.20 p.m. on Saturday 21st June 1919, the peace of Scapa Flow was broken by the clanging of a ship’s bell. It came from the battleship SMS Friedrich der Grosse, the former flagship of the German High Seas Fleet, interned in Scapa Flow and awaiting its fate to be decided at the peace talks that would officially end World War I. The bell signalled the crew to ‘abandon ship’; they had opened the sea-cocks and ‘scuttles’ (portholes that could be opened for ventilation) and jammed open the watertight doors, allowing the sea to flood the ship. By 5.00 p.m. 52 of the 74 ships of the former German Navy lay on the seabed.

While the interned fleet was provided with food from Germany, it received water from Stromness, carried in small vessels like the Flying Kestrel, which was on contract to the Admiralty from the White Star Line. On that fateful day the Flying Kestrel was playing host to a group of children from the Stromness Public School, later Stromness Academy. The vessel was sailing around the huge warships when they started to roll over and sink. The Flying Kestrel turned around and headed back to Stromness, where anxious parents were waiting on the pier. Some of the children cried while others cheered, thinking that this thrilling spectacle had been laid on for their entertainment. One elderly lady, who had been a child on board the Flying Kestrel that day, was asked about her abiding memory of the event. She replied, “Oh, the chocolate biscuits!” Such things were a rare treat in those days of post-war austerity.

The Stromness Salvage Syndicate was the first commercial company to purchase a German wreck from the Admiralty. It was formed by a group of enterprising local business men, who bought G89, a German Destroyer which was beached on the island of Cava. They managed to re-float the vessel and towed it to Stromness harbour where it was largely dismantled, and the valuable scrap metal sold.

During the 1920s and 30s a series of scrap metal merchants moved into Scapa Flow and started to make serious money from the sunken ships. This gave lucrative employment to many Orcadians and also access to other resources. Later it would create a whole new tourist attraction for sports divers, inspired by books like ‘The Grand Scuttle’ by Dan van der Vat, who learned of the story while visiting Stromness Museum.

Scapa 100 is the community based commemorations led by the Scapa 100 Initiative and Stromness Museum. From the 15 – 27 June 2019 we reflected on what was the largest loss of shipping, to happen on one day, ever. Spanning a whole year, from November 2018, when the German High Seas Fleet was interned in Scapa Flow, the commemorations take in the anniversary of the scuttling of the German fleet on 21 June and will end with a conference from the 17 - 20 October.