Learn to make a right use of your eyes; the commonest things are worth looking at – even stones and weeds, and the most familiar animals.

Hugh Miller was a stonemason, geologist, writer, poet and journalist. He was born in Cromarty in 1802 and died, by suicide, in Portobello, Edinburgh in 1856. It is difficult to overstate his importance to Scottish society of this period. He was noted not only as fossil collector, and in aiding the discovery of how rocks were formed over time, but also as one of the main leaders of The Disruption, the split in the Church of Scotland in 1843, bringing into being the Free Church. He was editor of the newspaper, The Witness, writing around 10,000 words a week and wrote several books including an autobiography, a collection of folk tales, and descriptions of his exploration of the rocks in various parts of Scotland.

In 1846 Hugh Miller visited Orkney and labelled it the ‘land of the fishes’, so numerous were the fossiliferous deposits he found. He describes this trip in Rambles of a Geologist, and what he discovered whilst here in Footprints of the Creator or the Asterolepis of Stromness. In Rambles he covers in some detail how he came by the asterolepis, the fossil that he wanted kept in Stromness, and which is now called ‘homosteus milleri’ and displayed in the fossil cabinet in the museum. He says,

I walked out towards the west, to examine the junction of the granite and the Great Conglomerate, where it is laid bare by the sea, little more than a quarter of a mile outside the town…And little more than a hundred yards over the granite, and somewhat less than a hundred feet over the upper stratum of the Great Conglomerate, I found what I sought, a well-marked bone, perhaps the oldest vertebrate remain yet discovered in Orkney, embedded in a light grayish-coloured layer of hard flag.

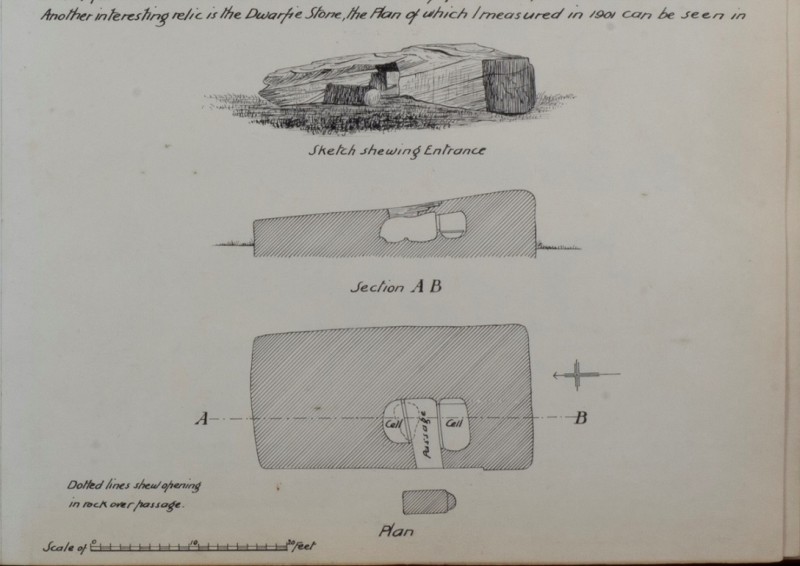

Miller’s writing is remarkable in that it mixes science with descriptions of place and nature and his own thoughts and feelings. It brings to life the objects which he found and gives them context, showing both their scientific and personal significance. While in Orkney, he visited Hoy and, to shelter from the rain whilst walking, crawled inside the Dwarfie Stane. His description of what he felt, thought and did there, is one of his most evocative passages. Here is a brief extract,

The rain still pattered heavily overhead, and with my geological chisel and hammer I did, to beguile the time, what I very rarely do - added my name to the others, in characters which, if both they and the Dwarfie Stone get but fair play, will be distinctly legible two centuries hence. In what state will the world then exist, or what sort of ideas fill the head of the man, who…will decipher the name for the last time, and enquire mayhap, regarding the individual whom it now designates…

A Sketch of the Dwarfie Stone in George Ellison’s journal (c) Stromness Museum - https://my.yupub.com/?tid=227bd7e9-e96b-41a8-9c66-24ebd72d8ace&pg=0#/page61

A question hangs over why Hugh Miller ended his own life – was it perhaps because he couldn’t reconcile his findings about how the world was formed with his biblical beliefs, or was it a mental illness brought on by overwork? Whatever the reason, his remarkable legacy, for some periods neglected, is significant as an inspiration to take notice of the world around us, wherever we are.