Introduction

Scapa Flow is one of the world's largest natural harbours and contains around one billion cubic litres of water.

It is a diver's paradise full of shipwrecks. But for those who don't venture beneath the waves, many of the natural wonders of "the Flow" are hidden.

This online exhibition introduces some of the fascinating, spectacular, and sometimes rare marine organisms which live on and around the wrecks.

Geological origins

During the last Ice Age heavy glaciers scoured Orkney’s 400-million-year-old rocks to shape our landscape and create the deep basin which now contains Scapa Flow. At about 60 metres, the deepest part of the Flow – the Bring Deeps – is thought to have been a glacial lake. Subsequent sea level rise flooded this ancient landscape to give Orkney’s characteristic pattern of firths between islands.

Natural harbour at war

The sheltered waters of Scapa Flow have been used as a safe haven since prehistory.

Human activity and diverse marine life have co-existed and influenced each other ever since.

Blockships were sunk in several entrance channels during the First and Second World Wars to prevent enemy submarines entering the harbour.

The Churchill Barriers were built along the Flow’s eastern margins for the same purpose.

These physical barriers have altered the tidal flow of water in and out of Scapa Flow.

Living wrecks

The remaining wrecks of the impressive German High Seas Fleet have changed the underwater seascape.

These ships, and their salvage sites, as well as plane wrecks and submarine defence booms have all created artificial reefs by providing a solid base for animals and plants to settle on.

They have also created areas on the seabed which are less exposed to disturbance from fishing gear and natural currents.

Balancing act

The marine creatures and habitats of Scapa Flow exist alongside a range of human influences, such as regular ferry and shipping movements, commercial fisheries, fish farming and recreational activities.

Since the 1970’s Scapa Flow has hosted the Flotta Oil Terminal’s crude oil transfer operations and now also provides Orkney’s European Marine Energy Centre with a test site for new wave energy devices.

A window on an underwater world

The Flow is renowned as a diving mecca, attracting divers from all over the world to explore the wrecks and associated marine life. Photos and video footage obtained by amateur and professional divers provide illuminating windows into Scapa Flow’s undersea world, for those who might otherwise never see it.

The following sections focus on a few of the specific wreck sites and showcase some of the spectacular animals and plants that live on or around them.

Click on the sections below to find out more!

Wreck: SMS Karlsruhe

Location: Northeast of Cava

Depth: 17-27 metres

Habitat type: Horse mussel bed

Featured species: Fan mussel

The SMS Karlsruhe is one of the German High Seas Fleet, which was salvaged in situ, by blasting with explosives (rather than being re-floated). This has made it very interesting to dive, as a lot of the internal parts of the ship can be easily seen. The ship is in relatively shallow water, which means sea life is abundant.

The wreck of the SMS Karlsruhe provides shelter for a highly valued marine habitat: horse mussel beds. Since it was scuttled 100 years ago, the ship’s presence has protected the surrounding seabed from trawling and dredging activity by fishing boats.

Fishing activity has also been minimised in the immediate vicinity, because of the daily visits from recreational dive boats.

Horse mussel beds are a UK BAP (Biodiversity Action Plan) priority habitat, which means they are considered to be vulnerable and requiring conservation. The mussels bind themselves to the seabed and each other with strong ‘byssus’ threads.

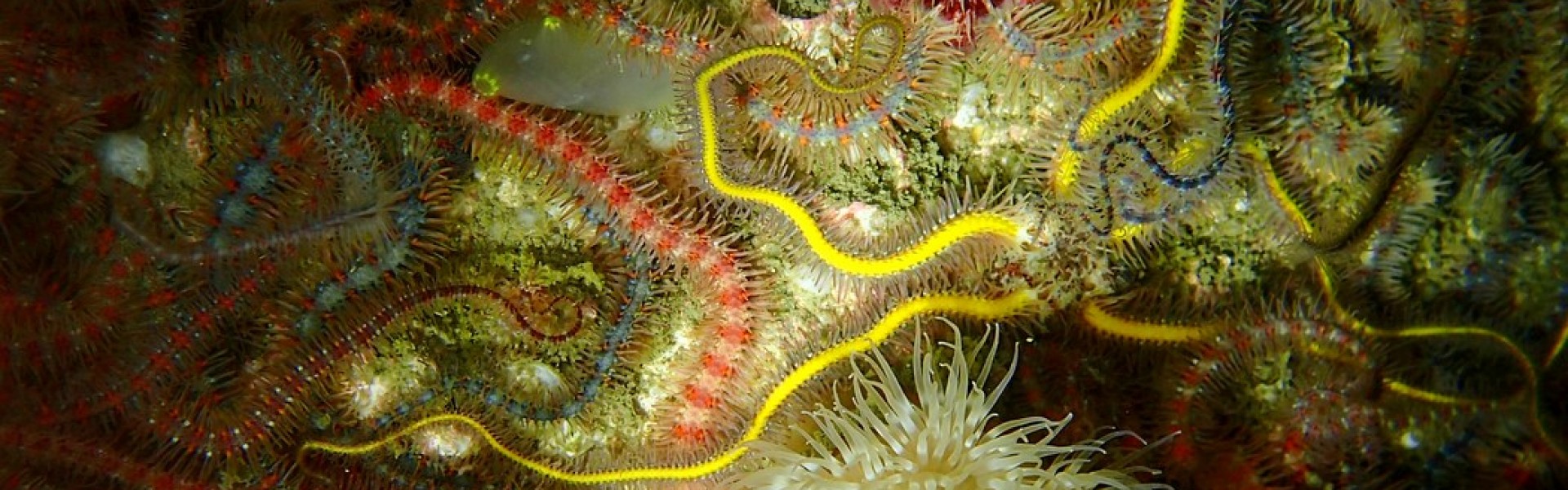

The beds are particularly good for providing shelter for numerous other animals, such as brittlestars, crustaceans, worms and molluscs.

They also act as a nursery for young whelks and scallops, both of which are important for commercial fishing.

The real jewel in the crown of the horse mussel beds at SMS Karlsruhe was discovered in 2011: a live fan mussel.

Fan mussels are one of the rarest shells in the UK and are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act because of their national importance.

The shells can grow almost half a metre long and live for up to 32 years.

According to fishermen’s lore, fan mussels should be cast back into the sea if they’re caught, as they feed on the remains of dead sailors.

Fishermen believed this because the byssus threads look remarkably similar to human hair.

The threads can be woven into a beautiful golden cloth, and this weaving still takes place today on the island of Sardinia.

You can read more about the exciting live fan mussel discovery in Dr Joanne Porter's guest blog.

Wreck: SMS Dresden

Location: East of Cava

Depth: 22 metres

Habitat Type: Wreck structure

Featured Species: Feather-star shrimp

SMS Dresden is a paradise for the feather-stars, which cling to the wreck itself. Feather-stars are a type of crinoid and are related to starfish and sea urchins. They have five pairs of feathery arms, which can be used for swimming. On SMS Dresden a rare discovery was made by visiting diver Rachel Shucksmith in 2013, when she saw a feather-star shrimp hiding, brilliantly camouflaged in the feather-stars for protection against predators.

The shrimp Hippolyte prideauxiana is very rarely recorded in the UK and sightings in Orkney and Shetland, have expanded its range by 400 km.

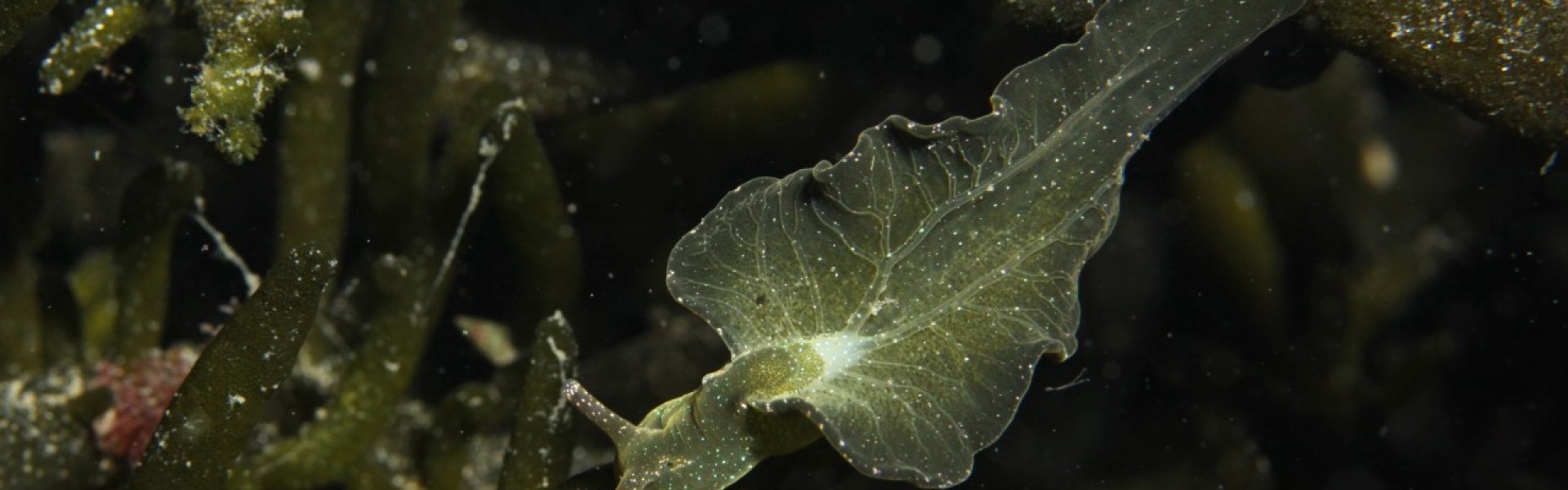

Another camouflaged creature, which lives on SMS Dresden is the sea slug Jorunna tomentosa.

It feeds on the sponge Haliclona, which has the same creamy colour and velvet texture as the slug.

Sea slugs are shell-less relatives of familiar marine creatures such as winkles and cowries (groatie buckies).

Wreck: SMS Moltke Salvage site

Location: West of Cava

Depth: 16 metres

Habitat type: Flame shell beds

Featured species: Flame shells

The salvage of SMS Moltke took place in June 1927, but it was not straightforward, as the ship’s superstructure kept getting stuck on the seabed. The operation left lots of debris on the bottom of Scapa Flow to the west of Cava. The wreckage appears to act as an obstacle, in which drifting seaweed gets caught up. To the untrained eye these piles of red seaweed look fairly uninspiring. However, they are formed into deliberate creations by a rare and fascinating mollusc: the flame shell.

The vibrant flame-coloured tentacles of the shell were discovered in Scapa Flow by Seasearch volunteer divers in 2013, when they lifted up some of the seaweed.

The flame shell builds the seaweed into ‘nests’ which offer it protection from predators.

Like the fan and horse mussels, the flame shell creates a network of byssus threads, binding with other shells, stones, and maerl if available.

Its nests can become quite complex and can have numerous galleries and ventilation holes.

They also provide a habitat for many other animals and plants to live in, greatly boosting biodiversity.

For this reason flame shell beds are listed as a Priority Marine Feature by Scottish Natural Heritage and a UK Biodiversity Action Plan habitat.

The flame shell feeds on plankton, bacteria, and detritus using its orange tentacles.

The tentacles provide a meal for predators such as the velvet crab, but the flame shell can detach some of its tentacles and escape from being entirely eaten.

The tentacles also contain a toxin which is unpalatable to some predators.

Wreck Site: Wildcat JV571

Location: South east of Cava

Depth: 35 metres

Habitat type: Sandy mud

Featured Species: Slender sea pens

An aircraft carrier HMS Trumpeter was moored just south of Cava on 2nd December 1944.

Due to a catapult failure, one of her aircraft, a Grumman Wildcat, fell over the port side. The pilot was rescued, but the plane was lost.

Thanks to the dedicated research of ARGOS (Aviation Research Group, Orkney and Shetland) and sidescan survey technology from SULA Diving in Stromness, the wreckage of the lost Wildcat was located on the bottom of Scapa Flow in 2014.

Nowadays the area around the wreckage is home to some unusual looking animals.

On the sea floor around the plane, divers encounter a forest of slender sea pens.

So-called because it looks like an old-fashioned feather quill, the sea pen is actually a colony of polyps which work together to function as one organism.

It digs a burrow in the seabed and can retract into it when threatened.

A rarely-recorded sea slug Armina loveni is a predator of this particular species of sea pen and has been seen in the sea pen forest near the Wildcat. Very unusual for a sea slug, it buries itself in the seabed to hide, whilst digesting the stinging cells of the sea pens.

So what's the future hold for these incredible marine organisms which live on and around Scapa Flow's wrecks?

Ecological Recording and Monitoring

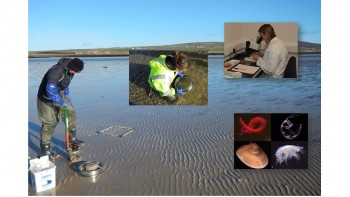

Many of the species mentioned in this exhibition would not have been recorded, without the dedication and skill of Seasearch divers.

Seasearch is a project for volunteer scuba divers who have an interest in what they're seeing under water, want to learn more and want to help protect the marine environment around the coasts of Britain and Ireland.

The main aim is to map out the various types of seabed found in the near-shore zone around the whole of Britain and Ireland.

In addition, Seasearch are recording what lives in each area, establishing the richest sites for marine life, the sites where there are problems and the sites which need protection. Seasearch is partly funded by the Marine Conservation Society and Scottish Natural Heritage.

The Marine Environmental Unit at Marine Services, Orkney Islands Council, was set up in 1974, following the Environmental Impact Assessment of the proposed Oil Terminal at Flotta.

Since then, the Unit has been monitoring the marine environment of Orkney.

The long-term monitoring within Scapa Flow includes; sandy shore, rocky shore, non-native species, toxic phytoplankton and radiological monitoring.

The Marine Environmental Unit also carries out microplastic monitoring with Heriot-Watt University.

Microplastics

In recent years the global problem of plastic in our oceans has received much media coverage.

A conservative estimate is that 5 trillion pieces of microplastic (measuring under 5 millimetres) are floating in the sea.

As well as the microplastics monitoring being carried out by the Marine Environmental Unit, new microplastics research is being carried out by Heriot Watt’s Orkney campus.

Microplastics can be tiny pieces of polythene bag or drinks bottles and even small fibres from rope or clothing.

Heriot Watt student, Rachel Layfield-Carroll, has been looking at the microplastics found in fish in Orkney’s waters. Notably, all the fish sampled had microplastics present in their guts and gills.

The plastics get passed up the food chain when the fish are eaten by predators like seals and humans.

We can all play our part in reducing the amount of plastic ending up in the sea, for example, by responsibly disposing of our own waste and by picking up litter on the beaches.

Through Orkney’s ‘Bag the Bruck’ events, we can all make an ongoing positive contribution.

Blue Carbon

Marine habitats are playing an important role in tackling climate change, by storing ‘blue carbon’.

It is widely known that trees and other green plants absorb the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. However, we are only beginning to appreciate the potential of the world’s oceans for absorbing and storing carbon.

For example, worldwide, seaweed alone captures an estimated 634 million tonnes of CO2 per year, greater than the CO2 emissions of Australia.

Orkney is now at the centre of new research – as the location for the world’s first region-wide blue carbon audit.

Scapa Flow has many habitats which will be covered as part of the audit. Kelp forest, maerl beds, seagrass meadows, salt marsh, horse mussel reefs and flame shell beds, as well as carbonate sediments, all play a part in storing blue carbon.

The work being carried out for Orkney will help put these habitats into the blue carbon context and shape future strategies.

Acknowledgements

This exhibition was put together as part of Stromness Museum's Scapa 100 commemorations in 2019, to mark the scuttling and raising of the German High Fleet in Scapa Flow.

We would like to thank our partners, in particular: Dr Joanne Porter at Heriot-Watt University; Alison Skene, Orkney Natural History Society Trustee and Penny Martin from Orkney Sub-Aqua Club for developing the content of the exhibition. We are also very grateful to Dr Angela Capper (Heriot-Watt), Jenni Kakkonen and her team (OIC Marine Services) and Gareth Davies (Aquatera) for their input, as well as many other generous contributors.

Funding has been provided by Museum Galleries Scotland and Cooke Aquaculture.

Finding out more

f you want to learn more about marine zoology, you can visit the museum in person and see our extensive Natural History collections for yourself!